Fundamental rights can collide in practice, even if constitutional norms are not structured hierarchically. When rights come into conflict, the principle of proportionality serves as a key mechanism for resolution, involving a careful assessment of adequacy, necessity and balanced consideration. A jurisprudence[1] particularly the Supreme Court Court[2]The International Court of Justice has recognised the direct effect of fundamental rights on private relations, although international legal literature continues to debate the extent and scope of such application. Practical examples include tensions between freedom of the press and privacy rights, limitations in critical situations such as kidnappings, and the adjudication of complex scenarios in the contexts of employment, family and property. Academics such as Sarlet, Canotilho and Rolim have extensively investigated these dynamics, emphasising the nuanced approach needed to optimise the protection of rights while preventing disproportionate restrictions on individual freedoms.

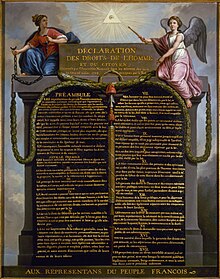

Fundamental rights are rights of the human being recognised and positive in constitutional law positive of a particular State (national character). They differ from human rights - with which they are often confused - insofar as human rights aspire to universal validity, that is, they are inherent to every human being as such and to all peoples at all times, and are recognised by the United Nations. International Law through treated and therefore has validity regardless of its positivisation in a given constitutional order (supranational character).